The play debuted in New York in 2001 with a pair of actors, and returned in 2005. But in this revival, a co-production of BAM’s Next Wave Festival and the Irish Arts Center, directed by Mr. O’Rowe, the indefatigable Tom Vaughan-Lawlor plays both ruffians.

The pavement-roughened poetry that surges and tumbles from his mouth is comic and wildly profane — take out all the filthy words, and barely a sentence will stand unmangled. But for all its rudeness and lewdness, it’s somehow epic, too, closing with the sort of tragic reckoning that an epic demands.

Though it builds to a conclusion so gore-spattered that it might make even Homer feel a little queasy, it begins innocuously enough. The Howie Lee (Mr. Vaughan-Lawlor in a maroon T-shirt) suddenly appears on the bare stage, undecorated save for a horizontal strip of light on the back wall. The Howie is a junior hooligan, good with his fists, bad with the ladies. Without preamble, he vaults into a story about crossing a field and spying a friend burning a mattress. Soon this friend draws him into an unlikely vendetta against the man, The Rookie Lee, who must have infested that mattress with scabies. Later that day, The Rookie Lee gets a comprehensive pounding. The Howie Lee returns home to something worse.

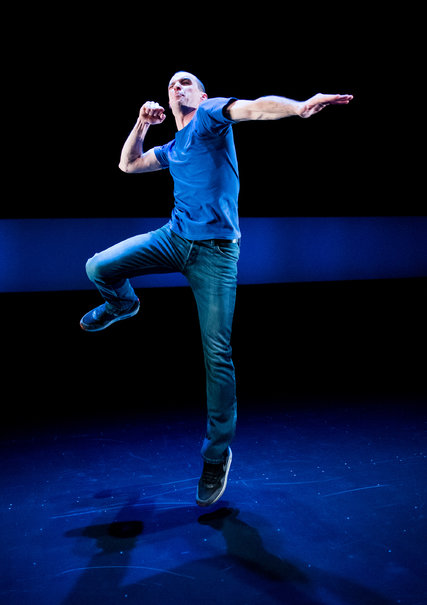

After The Howie Lee concludes his tale, there’s a very brief pause. (Let’s hope that Mr. Vaughan-Lawlor spends it rehydrating; he sweats enough to fill a kiddie pool.) Then The Rookie Lee (Mr. Vaughan-Lawlor in a periwinkle T-shirt) strides on, taking up the story from where The Howie Lee left it. A smoother and handsomer sort, The Rookie Lee breaks “hearts an’ hymens.” But he’s in awful trouble, having crushed a pair of prize fighting fish, pets of a psychopath named Ladyboy. His attempts to make reparations culminate in an extravagant melee.

Whichever shirt he wears, Mr. Vaughan-Lawlor doesn’t look much like an adolescent tough or a matinee idol. A retreating hairline frames a high widow’s peak; deep folds arc down toward a girlish mouth and a long neck with a prominent Adam’s apple. But as soon as he begins to move and speak, those features fade. His face becomes a screen onto which he can summon anyone he likes.

What’s most extraordinary about his acting is how little he seems to do. There are no spectacular transformations of face or voice or gesture, only subtle alterations. But these slight shifts clearly demarcate any of a dozen characters, male and female, old and young.

I’m not sure that having the same actor play both roles makes sense thematically. The unlikely friendship that arises between these unrelated Lees seems a lot more likely when the same actor plays both, but the performance Mr. Vaughan-Lawlor gives is sad and joyful, somehow meticulous and improvisatory at once.

And yet, he isn’t really the star of the show. The big dressing room at BAM Fisher should rightly go to Mr. O’Rowe’s live-wire language — lyrical and dirty and riotously imaginative. You can hear echoes of Joyce in the frequent neologisms — skullduggerous, popsock, dollyness — and maybe a hint of David Mamet in the obscene words and staccato rhythms.

You might also catch snatches of Mr. O’Rowe’s contemporaries Martin McDonagh in the wild, almost farcical violence, and Conor McPherson in the stealthy emphasis on moral choice and responsibility, as when The Rookie Lee worries over his fate.

“I never did anything that bad,” he equivocates. “I never hurt anyone. Maybe a couple of dollies. Emotionally. Unintentionally.”

But for all these literary correlations, Mr. O’Rowe’s language is distinct — in its ribaldry, its understatement, its metaphors and, especially, its exuberant, muscular descriptions of impossible battles. I’m not sure which Parnassian Muse inspires poets to such linguistic heights of gusto and grotesquerie. The least Mr. O’Rowe can do is give her a thanks in the program.

DEC in The New York Times 12, 2014